As the protracted fight over the shape of higher education comes to a head this month, a story comes to mind that might help illuminate the reasons behind the intensity of the effort to merge Rutgers-Camden into Rowan University.

In the last contested national political convention in modern history—the GOP convention in Miami in 1968—Governor Nelson Rockefeller’s operatives were jubilant to discover as the first ballot neared that they had stopped Richard Nixon some dozen votes short of the nomination, assuming New Jersey Senator Clifford Case continued to hold the state

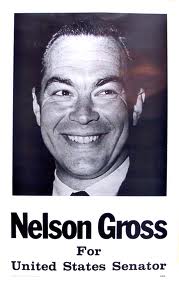

delegation behind his favorite son candidacy. Once they conveyed this news to the New Jersey delegation, however, they were startled to witness 18 votes, headed by New Jersey GOP State Chair Nelson Gross, switch to Nixon, thereby dashing once and for all Rockefeller’s chance at the presidency.

delegation behind his favorite son candidacy. Once they conveyed this news to the New Jersey delegation, however, they were startled to witness 18 votes, headed by New Jersey GOP State Chair Nelson Gross, switch to Nixon, thereby dashing once and for all Rockefeller’s chance at the presidency.

I recount the story, not as a reminder that Gross was subsequently awarded a Republican Senate nomination. Rather, I want to point out how important blocs of votes can be in determining the outcome of political contests.

There has been little doubt from the outset of the controversy that the proposal to fold Rutgers-Camden into Rowan came from Cooper Hospital Board Chair George Norcross and that he, together with Cooper President John Sheridan, were the takeover’s most forceful and consistent supporters. For his part, Governor Christie remained steadfastly behind the proposal, even though he did very little himself to actively promote it. Indeed, he seemed simply uninterested in providing a rationale that could only come from a thorough assessment of costs and benefits. Was it that so little was at stake? Hardly.

As a number of people have pointed out over the past few months, as long as the governor’s party remains in the minority, he depends on Democratic votes to get what he wants. He can veto legislation he doesn’t like, such as the bill approving gay marriage, but in one issue particularly—budget—he has to rely on a majority of votes in both branches of the legislature. Last year, South Jersey Democrats under Norcross’s control provided the votes the governor needed to roll back state benefits. This year, Christie counts on support for a tax cut, which he has made the keystone in the package of “reforms” he is using to sell his agenda in New Jersey and, indirectly, to a national GOP audience. When he has insisted time and again the changes he has proposed for higher education will go into effect by July 1 or they won’t happen at all, he is reminding South Jersey’s Democrats that their hopes for a merger in South Jersey are tied to the budget deadline.

Because Governor Christie was thwarted in his initial plan to execute a reorganization of higher education by executive order, he now counts on Steve Sweeney, as leader both of the Senate majority and South Jersey Democrats, to effect some form of the merger through legislation, no easy task as northern Democrats make their own demands for changes in the initial Barer proposal. The challenges posed in striking a deal that will satisfy Democrats in all parts of the state have delayed the introduction of a bill. If compromise goes too far, Sweeney risks losing the governor’s support. In the meantime, however, he still has the votes the governor needs to get a budget he can live with. Both the governor and his South Jersey Democratic allies thus have every incentive in the world to continue working to implement some form of the Barer proposal.

That’s why the news that Rutgers’ two boards of trustees are on the verge of blocking any form of severance of its Camden campus is so important. If they act, as reports say they are prepared to do, then neither the governor nor the legislature can override the university’s control of its own assets as established under the 1956 act that established Rutgers as the state university. That doesn’t mean that reorganization in higher education would be dead, only that it would take a different form. In South Jersey, where the proposed takeover remains wildly unpopular, that would be welcome news. New Jersey may have given us Richard Nixon in 1969. It can give us something better in 2012.

It may be too late to bring this up, but the public has never been given an adequate explanation why Rutgers turned down one or more attempts by George Norcross to get Rutgers involved in the new Cooper Medical School. (prior to the Rowan’s involvement). According to a recent New Jersey Business newsletter a high level Rutgers administrator was charged with scouting out the new Cooper Medical School and given the responsibility of making a recommendation to the Rutgers administration in New Brunswick. This newsletter came closest to uncovering the story, but left out key details. The scout’s recommendation was that Rutgers should to get involved with the new Cooper Medical School at an estimated cost of $15 million. The administration in New Brunswick punted.

If any of this is true, then what would someone expect from George Norcross as a reaction to such a rejection? Rutgers has two law schools. There is no reason Rutgers could not have two medical schools, Cooper and Robert Wood Johnson. If I had been President McCormick I would have said to George Norcross, “George this is going to take a significant amount of money and Rutgers is interested in the Robert Wood Johnson Medical School. Help me get the money from the Legislature so Rutgers can become partners in both Cooper Medical School and Robert Wood Johnson.”

The public is turned off by secrecy as a method of deciding the fate of higher education in the New Jersey. If the Rutgers administration punted when they should have gone for the first down, then Rutgers should rectify that. It appears the Rutgers Boards are engaged in doing just that.

Of course there may be other possible motives for a Rowan/Rutgers merger in South Jersey such as a source of patronage jobs, awarding contracts to a cabal of consultants, bond counsels, lawyers, accountants & finance firms, architects & engineers, bond underwriters, insurance carriers, construction firms, etc. And a new governing Board to award those contracts.

With the completion of the Revel casino in Atlantic City there is not a lot of construction work in South Jersey for union tradespeople such as iron workers and other unionized trades (among Senator Sweeney’s constituency) that by law have to be used on State building projects. What better way to provide construction jobs than to expand the Rutgers Camden campus? Everyone agrees that South Jersey has been short changed in higher education funding.

As you point out, a relatively small band of legislators can have an enormous impact if they cut a deal with the opposing party. Finally the proposed $6 billion dollar bond issue for higher education in New Jersey shows a lot of chutzpah on the part of somebody. I find it ironic that Princeton University, ranked number 5 in the world, has no medical school.

James Schwarzwalder