Normally the announcement of D.C.’s five-year economic strategy would scarcely cause a stir as the stuff of bureaucratic necessity, in this case, fulfilling requirements for acquiring federal grants. But the “Comeback Plan” announced last week is different, as a test whether the District’s post-pandemic era will effectively address the profound effects both of Covid and the renewed cry for social justice.

It’s no secret that before the pandemic Washington was among the nation’s leading cities in reversing years of economic decline through robust revitalization. Private investment was up, as were property values and revenue. But progress was not without its costs, as gentrification spread and the stock of affordable housing and rents plummeted.

To its credit, the city created an affordable housing fund to address the problem. It also established an office of equity intended to assure access for those in greatest need. The new economic plan, with its goals of increasing minority-owned business and lifting Black resident median household income, clearly recognizes the problem. But are the tools there to balance “progress” with the needs of those struggling with poverty? The strategy’s emphasis gives cause for concern.

Early in the new century Mayor Anthony Williams set a goal of attracting 10,000 new residents to Washington, an objective the city achieved. But instead of the anticipated arrival of families, the great majority of newcomers were either adults over 55 without children or young and childless, the very millennials every city was striving to attract. Post-Covid, many of those millennials are gone, and the city in setting a goal of 25,000 new residents hopes to bring them back by relying on the same formula that many cities have employed by making downtown a great place to work, live, and play. Such was the rationale of the tax abatement program announced last month.

Just such a program heated up downtown Philadelphia in recent years, but with unintended effects as demand spread to inner city neighborhoods to the north and south. Oakland too set a goal of 10,000 new residents in the 1990s, and it has grappled with the ill effects of gentrification ever since.

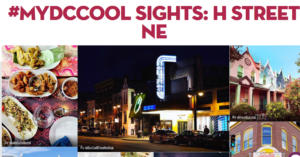

No doubt revitalizing downtown Washington is a worthy goal. But it’s clear that the intent is to remake the physical landscape to accommodate younger, hipper residents, much as the H Street corridor was remade and rebranded in the Northeast as the Atlas District, marginalizing in the process nearby Black residents who had relied on the area for primary shopping needs for most of a generation.

Washington’s doesn’t need to reignite the investment flurry of the first twenty years of the century. To assure justice as well as greater vitality downtown through subsidies to investment, it needs additional tools to complement those that have been on the books, like the Tenant Opportunity to Purchase Act, which has had only limited success in stemming displacement in the years since it was instituted in 1980.

No doubt community organizations will step up their drive for equitable policies, but DC can prove a good partner by consciously linking new investment to broader social goals. The office of Planning oversees the strategic economic plan, and zoning plays a crucial role in land use decisions. It remains to be seen whether that tool will be used more consistently to advance equity. Other measures, such as inclusionary housing measures and real estate transfer taxes dedicated to affordable housing, could also help. Whatever measures are employed, Washington needs not just to bring back its downtown but to make sure that its neighborhoods are not undercut in the process.