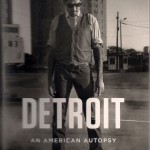

Now that Michigan has stepped in to take over the city of Detroit, we can expect even more commentary on the city and its dismal condition. In that process, there is bound to be further comment about Charlie Leduff’s Detroit: An American Autopsy, which quickly ascended onto the New York Times bestsellers list after it was reviewed in The Times in February. One of the early comments on Detroit native-turned newsman Leduff’s book came from Fred Siegel, a frequent contributor the conservative Manhattan Institute’s publication, City Journal. Siegel called the book “marvelous,” choosing to blame “the intersection of unprecedented prosperity and cultural liberation” for wrecking havoc on LeDuff’s “once-solid working-class family”: the murder of his sister turned prostitute, the death by overdose of his “stoner niece,” and a brother lingering “in a crack den.”

Now that Michigan has stepped in to take over the city of Detroit, we can expect even more commentary on the city and its dismal condition. In that process, there is bound to be further comment about Charlie Leduff’s Detroit: An American Autopsy, which quickly ascended onto the New York Times bestsellers list after it was reviewed in The Times in February. One of the early comments on Detroit native-turned newsman Leduff’s book came from Fred Siegel, a frequent contributor the conservative Manhattan Institute’s publication, City Journal. Siegel called the book “marvelous,” choosing to blame “the intersection of unprecedented prosperity and cultural liberation” for wrecking havoc on LeDuff’s “once-solid working-class family”: the murder of his sister turned prostitute, the death by overdose of his “stoner niece,” and a brother lingering “in a crack den.”

One suspects LeDuff, had other targets than cultural liberation in mind. His is a grim tale of government incompetence and stunning indifference to the consequences of the collapse not just of the private but the public sector.

The book opens with the discovery of a body frozen over a number of weeks in the shell of a building that was accumulating enough water in its basement to afford iceskating within its walls. It turns out that the body, which was fully encompassed in ice except for two protruding feet, had been sighted some time earlier but not reported. LeDuff calls 9/11 only to be told they couldn’t be bothered, and it takes even more time before the body is finally removed.

LeDuff relishes the kind of hardnosed reporting he conveys in this book. His language is blunt. His observations are not analytical. Indeed, he is not able to escape the ill effects of his beloved dying city on himself. But like so many of the hardscrabble people who remain in the city, he’s willing to fight the bad odds.

In one of the few bright threads in the book, he recounts the winding path that finally brings to justice the man responsible for setting a fire in an abandoned building that is responsible for the death of one of the firemen called to extinguish it. “People often ask, where is the hope in Detroit?” he writes. “I had just watched it. Society had functioned properly in this case because we all wanted it to. The firefighters, the cops, the judge, the jury, the reporter.”

In essence, LeDuff had done his job, by prodding an investigation by authorities who otherwise might have let the whole matter go. It will be a lot harder for the state’s fiscal officer to right the city for the longterm. In the meanwhile, I can recommend LeDuff’s book. While it does not point the way to solutions, it serves as an important reminder of how deep the city’s malaise has become. There’s no guarantee the state will act responsibly or effectively, but LeDuff’s book helped convince me, as I’m sure it will others, that further inaction was not an option.