As the nation has revisited the glory days of the civil rights movement over the past year—the Civil Rights acts of 1964 and 1965, Freedom Summer, 1964, and Selma—we have been reminded of a special moment in time when a growing demand from whites as well as African Americans for equal justice overwhelmed resistance to create the possibility of a color-blind basis for citizenship

Fifty years after that tumultuous period, color-blind allegiances abound, yet evidence proliferates that our system is anything but equal.

That realization is especially painful for the privileged graduates of the mid-1960s at Yale who embraced as undergraduates hopes for “a more perfect union,” frequently putting their bodies as well as their souls behind that effort.

Yale students in the ‘60s were not alone, of course, in supporting civil rights efforts. Freedom Summer drew youth from around the country, as was so well documented in the 2014 American Experience documentary on the subject. But missing in that account was Freedom Summer’s prelude, a mock election held in Mississippi in the fall of 1963 to demonstrate that African Americans, were they allowed to vote for governor that year, would have done so. The idea, which emerged out of voter registration efforts led by the Student Non-violent Coordinating Committee, gained distinctive character under the leadership of Allard Lowenstein when he helped recruit students at Yale and Stanford to join the effort.

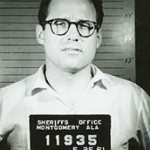

Bill Coffin, following his arrest as a Freedom Rider in Montgomery, AL, May 24, 1961

Yale chaplain William Sloane Coffin, a Freedom Rider in 1961—much to the consternation of many older alumni and a number of current Yale students—who had so much to do with raising awareness of civil rights issues on campus seized on the idea. Among those he recruited to travel south for a week in October, 1963, were Joseph Lieberman, the influential chairman of the Yale Daily News. Years later, his trip to Mississippi became a point of pride in his campaign for vice president on the Democratic ticket in 2000. Classmates still cited his 1963 editorial, “Why I go to Mississippi.”

Lieberman was joined by a number of other Yale undergraduates, a number of whom were physically threatened during their short stays in Mississippi. One of them, Steven Bingham, a fellow ’64 news editor, was jailed on false charges, along with Lowenstein in Clarksdale. On returning to Yale, he took a leadership role in organizing for Freedom Summer, ultimately rooming in Holmes County for some six weeks with Mario Savio, who soon thereafter became a prime instigator of the first nationally prominent student protest, the Free Speech Movement at Berkley.

Was it not especially ironic that another member of Yale ’64, William Bradford Reynolds, who also befriended Lowenstein and attended the March on Washington in 1963, became the object of intense criticism for attempting to roll back civil rights provisions such as busing and affirmative action in the name of the very color-blind ideal that had unified the early movement?

‘64’s Bill Drennen captures well the dilemma suggested in the evolution racially-conscious approaches to living, let alone citizenship, in his 2004 book, with Kojo (William T.) Jones, Red, White, Black & Blue, a brave attempt to bridge the substantial racial gap that remains 50 years after Drennen’s graduation from Yale. Despite similar backgrounds, the two men see the world very differently. While Drennen echoes Reynolds’ desire to for a color-blind society, Jones rejects the premise by writing, “’Let’s be a color-blind society, the even-steven concept. Let’s all put down our arms and start a fight here on a level playing field, as if integration and affirmative action have already accomplished their goals.’ This is an argument designed to appease whites. It employs the Abraham Lincoln philosophy on the slavery issue…and I suspect even Bill Drennen subscribe[s] to this kind of even-steven concept. This is the fallacious, illogical reasoning that is being used in most government circles as a way to keep the black minority from achieving economic parity. Sure. And then give us another two hundred fifty years to catch up.”

I take up these issues in my new book, Class Divide, suggesting in the end that a parallel can be drawn between the admission of these men to Yale and the Supreme Court support—to date—for the utility of affirmative action. Not all those who joined me in New Haven those years will agree, which is why it’s worth calling attention to the subject.