Judging from the symposium hosted on the Princeton University campus May 1st, the question at hand—“Could there be a New Jersey school of urban studies?”—is both timely and still to be determined. Presentations covering a wide range of topics, from segregated school houses to oral histories of “queer” Newark, proved stimulating, if not always directly on the topic at hand.

Judging from the symposium hosted on the Princeton University campus May 1st, the question at hand—“Could there be a New Jersey school of urban studies?”—is both timely and still to be determined. Presentations covering a wide range of topics, from segregated school houses to oral histories of “queer” Newark, proved stimulating, if not always directly on the topic at hand.

What came through, however, was the huge potential for collaboration among scholars from a variety of disciplines to engage some of the toughest questions facing contemporary America and the prospect of finding answers close at hand in New Jersey.

That potential was unveiled in the opening presentation, from Rafi Segal, an architect and Associate Professor of Architecture at MIT. Pointing to the core elements of New Jersey community formation, separation and segregation, Segal presented an elaborate set of physical and spatial configurations to further classify those communities. To combat the persistence of patterns of physical separation, he encouraged a process of “cross breeding” to create new forms of hybrids, a process he believes could be facilitated by advances in social media.

Although Segal was vague about what practical measures might be applied to transcend the differences that abound among New Jersey’s fiercely protective jurisdictions, the theme of addressing separation and segregation returned repeatedly during the day’s proceedings, undergirded by recognition that if New Jersey, by measure of average density of settlement, may be the most urbanized state in America, it is also the most suburbanized.

Typically historians have treated cities and their suburbs as natural antagonists and have less frequently sought to describe and analyze the nuances among as well as between different communities. Once one determines not to be bound by traditional labels or boundaries, then a whole range of significant questions open up.

Symposium organizer Johana Londono, a Mellon Fellow at Princeton and an Assistant Professor in the Department of Latin American, Caribbean, and U.S. Latino Studies at SUNY-Albany, suggested the possibilities of such work by linking factors that bound Latinos living together in Union City, New Jersey, to more cosmopolitan relationships with people and places outside their jurisdictional home. Implying differences between elective and forced segregation, she made a case for studying distinct populations without removing them from the influence of places where they live.

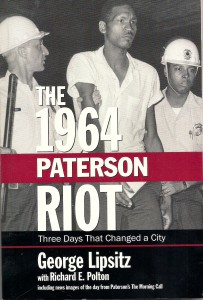

The tragic death of Freddy Grey and the violence that followed in Baltimore was very much in the air that day, and University of California at Santa Barbara professor George Lipsitz spoke eloquently to the unwanted stigmas that attach to people and places when such incidents occur. Drawing from a recent book he co-authored about the 1964 riot in his home town of Paterson, Lipsitz decried a long history of blaming civic disorder on bad behavioral patterns identified with areas of concentrated poverty rather than recognizing such behavior as reactions to legitimate grievances. Not incidentally, his remarks coincided with two perfect demonstrations of his theory in the New York Times: David Brooks’s column blaming Baltimore’s disturbances on a failure in social psychology, while a companion column by Johns Hopkins University historian N.D.B. Connolly declared, “Black Culture is not the problem.” Connolly’s remarks evoked a particularly intense response. His assertion that Baltimore’s problem stemmed from “the continued profitability of racism,”however, was confirmed in Lipsitz’s remark that too many people have “let racialized capitalism off the hook.”

The tragic death of Freddy Grey and the violence that followed in Baltimore was very much in the air that day, and University of California at Santa Barbara professor George Lipsitz spoke eloquently to the unwanted stigmas that attach to people and places when such incidents occur. Drawing from a recent book he co-authored about the 1964 riot in his home town of Paterson, Lipsitz decried a long history of blaming civic disorder on bad behavioral patterns identified with areas of concentrated poverty rather than recognizing such behavior as reactions to legitimate grievances. Not incidentally, his remarks coincided with two perfect demonstrations of his theory in the New York Times: David Brooks’s column blaming Baltimore’s disturbances on a failure in social psychology, while a companion column by Johns Hopkins University historian N.D.B. Connolly declared, “Black Culture is not the problem.” Connolly’s remarks evoked a particularly intense response. His assertion that Baltimore’s problem stemmed from “the continued profitability of racism,”however, was confirmed in Lipsitz’s remark that too many people have “let racialized capitalism off the hook.”

New Jersey’s highly particularized form of community formation, what one author has called “municipal madness,” offers a particularly rich field to test the relative importance of “place” among other factors influencing life course.

Brooks is not wrong, of course, in claiming that there has been a failure in socialization that has marginalized collective welfare in favor of short-term self-interests. In ghetto circumstances, these might appear self-destructive. In affluent suburbs they can appear self-serving. What conference participants implied last week is that one set of attitudes should not be evaluated in isolation from the other. Is it possible that aggressive behavior in a “ghetto” might be considered self-destructive, whereas the same behavior, when it results in a high standard of living in a “desirable suburb,” is admired?

It happened too that the symposium coincided with the 40th anniversary of the landmark Mount Laurel court decision in which the New Jersey Supreme Court, citing the need to affirm “the general welfare” as the state constitution defines it, overturned local zoning practices that had the effect of excluding affordable housing. In its declaration that every community assume its “fair share” of affordable housing, the court attempted to shift the burden of supporting the poor out of declining cities to the breath of the state. Suburban jurisdictions have been fighting the ruling ever since, a cause Governor Chris Christie has made a centerpiece of his administration, even has he has been blocked by the courts from shutting down the effort entirely.

As I indicated in my presentation on Camden, Christie’s stance is especially self-defeating given his determination to make new programs in the city, highlighted by generous tax credits, proof, as he said in his State of the State address in January, that if he can renew Camden, he can renew the country. Tax breaks to lure jobs into the city, without adequate funds to train the unemployed living nearby, is not a recipe for lowering the city’s extremely high concentration of poverty. An aggressive police force, armed with new tracking equipment, is not sufficient to lower crime to acceptable levels when hopelessness is confined and concentrated in a single city, largely removed from more affluent communities around it.

The question for those seeking a special New Jersey contribution to contemporary urban scholarship, is how to lay out a thorough basis for understanding the separation and segregation of New Jersey’s communities and the combination of policies and programs that might reasonably reverse the destructive pattern of human and physical disinvestment that have left Newark, Paterson, and Camden, among others, out of America’s mainstream social and economic systems. Such answers need not come from the social scientist’s quantitative measures alone. Case studies of lived experience open up new avenues for evaluation, as the presentations last week indicated. But a worthy objective of the Mellon initiative at Princeton is to seek the larger goal of understanding better how state, city, and suburb, with all their constituent elements, interact to produce a set of experiences that falls well short of any claim that America is the land of unbounded opportunity.