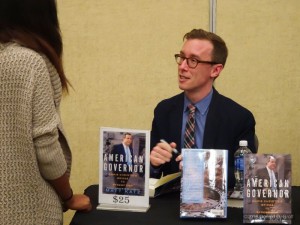

WNYC reporter and author Matt Katz reflected on Chris Christie’s relationship to Camden Tuesday. Drawing on years of coverage both of the city and of the governor, Katz conveyed a number of insights from his recently published American Governor: Chris Christie’s Bridge to Redemption in a talk on the Rutgers-Camden campus.

For those in the audience who lived through Christie’s effort to fold Rutgers’s Camden campus into Rowan University in 2012, there was no surprise in Katz’s contention that the effort, even though it failed, stemmed from a close association between the governor and the undisputed kingpin of South Jersey politics, George Norcross.

Photo courtesy Donald Groff

In fact, Katz builds much of his book around Christie’s deft transactional exchanges with the three big men in New Jersey Democratic political circles: Steve Adubato and Joseph DiVincenzo in North Jersey and Norcross in the southern part of the state. No doubt the support for Norcross’s dogged effort to acquire Rutgers’ resources to boost the new medical school in Camden affiliated with Cooper Hospital where Norcross is board chair, represented payback for the votes South Jersey Democrats delivered in the legislature to pass Christie’s early signature achievement requiring additional contributions from state employees for their benefits.

Not well known, however, was Katz’s revelation that the relationship formed even before the governor stepped into office. The two men reportedly came to a working agreement while attending a Phillies game in Philadelphia that was not recorded on the governor’s calendar.

The timing is significant because Democrats in the legislature removed state control of the city of Camden before the governor could take his oath of office. Katz didn’t immediately make the connection, answering a question Tuesday that the state takeover, which had another three years to go, was lifted because it was perceived to be a failure. In fact, many thought at the time that the move was made to prevent Christie from exercising the state’s extraordinary powers over the city. In light of Katz’s revelation, it’s more likely that Norcross seized the opportunity to advance his own agenda for the city, with the governor’s help and without the bother of citizen input required under state takeover legislation.

Katz’s own emphasis fell on the way Norcross cleverly used a new law introducing privately run but publicly funded charter, or “renaissance” schools, to get a building constructed with Norcross’s name on it around the corner from the hospital. This was a central but hardly singular instance where Katz details Norcross’s ability to realize his goals with help from Trenton. In fact, Katz tells a story that may have overstated the point, but not by very much.

Shortly after Norcross had become one of the owners of the Philadelphia Inquirer, where Katz was working at the time, the two men converged at the annual dinner of the state correspondent’s club. Katz was president that year, and he had the mic while Christie sat nearby at a table with the lieutenant governor, the Senate president, and the chief justice. After telling a lame joke about former governor Jim McGreevey, Katz moved into full roasting mode, remarking, “Governor, you and I do have something in common. As many of you know, my newspaper, the Inquirer, was bought by George Norcross one year ago….That’s right, Governor. You and I have the same boss…I don’t know what everybody is laughing at. He’s your boss too!”

In his years at the Inquirer, Katz had a reputation of being a little too easy on the governor. No doubt his statement at the correspondent’s dinner was offered in good fun and didn’t violate any pattern of friendly engagement, though Katz does not record the governor’s reaction. In this vein, much of American Governor is admiring, and Katz asserted at his talk Tuesday that he believes that no recent New Jersey governor has come close to exercising Christie’s political skills. Still, there is a critical undertone to his book that goes beyond the influence of the scandal associated with the George Washington Bridge, as important as he believes that event was in bringing Christie’s presidential aspirations to earth. What emerges is the portrait of a man whose ambition leaves virtually no available instrumentality untapped. One story Katz tells about Camden makes the point.

Following the scandal at the bridge, the governor turned his attention increasingly to Camden, manufacturing a host of feel-good moments and ultimately making the city the crux of his 2015 State of the State address by asserting that if he could renew such a devastated place he could renew America. With Norcross in control of local politics and massive tax credits luring businesses to relocate there, Christie was indeed a welcome presence in Camden. And he even seemed to enjoy the people, most particularly kids whom he tossed baskets with and cheered on the football field. Katz said he was particularly impressed that Christie, having had a nice photo shoot with the Camden High football team, actually made a huge effort to fulfill his promise to return to witness the big game against city rival Wilson later that year. He broke from campaigning in New Hampshire to charter a plane to Philadelphia, where a state vehicle rushed him across the Delaware River to the game. What Katz didn’t know at the time but discovered later was that Christie traveled with a Washington Post reporter to whom he had promised an exclusive story.

Christie emerges in Katz’s volume as something of a tragic figure: a man who flew close to the sun but who has since been forced back to earth. Camden has had its own moments over time. It remains to be seen, however, whether Camden and the man behind the largesse directed its way by the governor in recent years will sustain an upward path or in the aftermath of a failed presidential campaign, it will become what it has been so many times before: an afterthought to other ambitions.