Urbanists have long been critical of the deep subsidies directed at the construction of sports complexes for professional teams, often at the immediate expense of nearby neighborhoods, to say nothing of the drain on municipal budgets when costs inevitably outpace the presumed benefits of such investment.

In recent years, activists have fought back, aiming to assure that the benefits of redevelopment reach more widely into communities of need. In seeking clearance for Brooklyn’s Atlantic Yards basketball arena, famously, developers offered a set of benefits to local groups they assembled themselves, undercutting the very premise of inclusion at the heart of such agreements, as a recent report in the housing journal Shelterforce attests. In Milwaukee, negotiators attained better results in getting local residents of color hired in the construction and operation of the new Fiserv Arena. The Bucks still sought and received deep subsidies to underwrite the new complex. Now, two projects of vital concern are proceeding to test the premise in the aftermath of George Floyd’s death that public investment must be more equitably allocated.

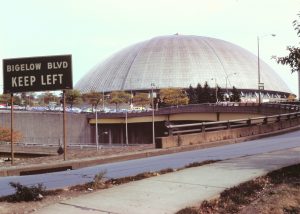

The redevelopment of the site where the Pittsburgh Penguins play has a long history at the lower end of the predominantly Black Hill district adjacent to downtown. The city’s first venture into the area, a civic arena originally slated for light opera until poor acoustics forced the departure of the orchestra and prompted control by the Penguins after their entry into the National Hockey League in 1967, displaced over 8,000 residents and hundreds of small businesses. When the Penguins threatened in 2007 to shift the franchise to Kansas City, Missouri, if public authorities did not provide the financial support needed to replace the Mellon Arena, as the old Civic Center had been renamed, community activists stepped in. Vowing “not to give away the Lower Hill again,” they determined that any new development would have to benefit the community as well as the prized hockey franchise. Building from a series of community meetings, area activists fashioned a community benefits campaign under the name One Hill Coalition, an umbrella that ultimately included close to a hundred separate organizations based in or supporting Hill residents. Their platform, Blueprint for a Livable Hill, emerged from priorities established by community vote. Agreement was finally reached in 2014, including some but not all of the priorities spelled out in the Hill Blueprint.

Pittsburgh’s Civic Arena, c 1990

With the Penguins’ shift to the new PPG Paints Arena in 2010 and demolition of the old structure, a prime site opened up downtown. Redevelopment stalled, however, after U.S. Steel withdrew its commitment to build a new headquarters there. It was only this September 1st that FNB (First National Bank) broke ground to anchor the site with a 26-story tower. Under the terms for redevelopment, the bank agreed, as part of the earlier community benefits deal, to advance $8 million in funding to be used for development in other parts of the Hill and another $3 million for Hill-related housing. There are also plans for the creation of a hiring center that could provide jobs for Hill residents as well as training for union trades work. Not incidentally, the bank also agreed to keep its national headquarters in Pittsburgh, receiving at least $10 million in state subsidies and purchase of the land from the Penguins, who continued to control development rights, for only $1.

Had there not been so many changes to plans over much of a decade, the benefits agreement signed in 2014 might have held, but over time some of those commitments eroded. While Pittsburgh’s Urban Redevelopment Authority approved the plan in May, it did not go without criticism from Hill leadership, and it remains unclear how fully the $50 million in promised investments, grants, and loans will materialize.

Proposed Oakland A’s ballpark

In Oakland, an even more dramatic contest is unfolding over the proposed construction of a new stadium and associated mixed use development on the waterfront. The city has already lost professional teams to San Francisco and Las Vegas. The A’s contend they can no longer live with the Coliseum’s outdated facilities in East Oakland. The team has proposed redeveloping that area as a mixed-use facility, with the old stadium serving community uses, while the team constructs a new facility adjacent to the tony Jack London Square on land owned by the Howard marine terminal. In addition to longshoremen who fear for their long-term survival as new development intrudes on port activity, area residents worry about the project’s effect on housing prices, which have been rising dramatically for a decade. To their credit, the A’s partnered with the West Oakland Environmental Indicators Project to fashion a community benefits agreement. While city officials withheld subsidies for the $12 billion project, the state legislature designated the proposed site as an infrastructure zone, making it eligible for subsidies for the transportation facilities essential to the project.

After Oakland’s city council, presented its terms for final approval in May, the A’s began to balk, a position that hardened after Alameda County reported it could not ensure its share of funding for infrastructure. With Major League Baseball’s encouragement, the A’s started to consider moving to Las Vegas, saying continued use of the Coliseum was unacceptable.

While it is clear redevelopment of the Lower Hill will continue, however deep or shallow the community benefits, the fate of the A’s proposal is less certain. Their ability to leave Oakland entirely reminds us how difficult it is to ensure equitable development when capital investment in sports is so mobile. That’s why the A’s decision—and the context in which it is made—should remain of special interest as the season plays out.