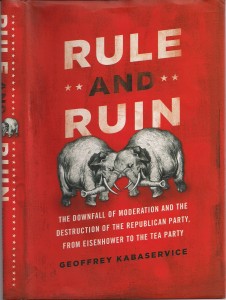

One of the most frequent charges Newt Gingrich lobbed against Mitt Romney in New Hampshire was that he is a “Massachusetts moderate.” Specifically Gingrich attempted to associate Romney with memories of the failed Democratic candidacies of Michael Dukaukis and John Kerry, throwing in the additional complaint that Romney ran to the left Ted Kennedy in his unsuccessful campaign for U.S. Senate. A more subtle message to GOP voters was to remind them of the lasting resentment against the Eastern liberal establishment, exemplified in Barry Goldwater’s 1964 presidential campaign and reiterated by conservatives ever since. But just as heavily weighted as a negative reference was the term “moderate.” Massachusetts was once the home too of moderate or liberal  Republicans: Ed Brooke, the first African American elected to the U.S. Senate since reconstruction, Elliott Richardson, and governors Frank Sargent and John Volpe, once considered a strong candidate to join Richard Nixon’s presidential ticket in 1968. If you wonder why the term “moderate” is such a signifier of particular ill repute, you might want to turn to Geoffrey Kabaservice’s Rule and Ruin: The Downfall of Moderation and the Destruction of the Republican Party, From Eisenhower to the Tea Party.” accorded front-page treatment in the January 8 New York Times Book Review.

Republicans: Ed Brooke, the first African American elected to the U.S. Senate since reconstruction, Elliott Richardson, and governors Frank Sargent and John Volpe, once considered a strong candidate to join Richard Nixon’s presidential ticket in 1968. If you wonder why the term “moderate” is such a signifier of particular ill repute, you might want to turn to Geoffrey Kabaservice’s Rule and Ruin: The Downfall of Moderation and the Destruction of the Republican Party, From Eisenhower to the Tea Party.” accorded front-page treatment in the January 8 New York Times Book Review.

Presumably Gingrich was not aiming his remarks at New Hampshire voters, considered among the more moderate in the GOP. Instead, he was seeking to separate Romney from the great bulk of GOP voters who will weigh in as the campaign shifts south and west.

Kabaservice reminds us that the GOP wasn’t always so far positioned to the right. Well into the early 1970s, moderates played a central role in Republican politics, especially in the recovery from Barry Goldwater’s devastating defeat in 1964 until Richard Nixon’s resignation a decade later. They hailed not just from the Northeast, but from all parts of the country, including the South. Among an especially able group of moderate governors was Mitt’s father, George. Kabaservice recounts, on page 130, an especially poignant exchange between the elder Romney and Goldwater after the 1964 election, in which Romney rejects the desirability of realigning the two political parties along European lines, as liberal and conservative. “Dogmatic ideological parties tend to splinter the political and social fabric of a nation, lead to governmental crises and deadlocks, and stymie the compromises so often necessary to preserve freedom and achieve progress,” he wrote. And yet, this is precisely what has happened.

In 2008, Mitt Romney recounted joining his father in a civil rights march in Michigan. The account proved inflated. No matter in 2012. The younger Romney is making no effort to associate with his father’s moderate credentials. The Republican party is too far right for that, but the contrast between father and son is instructive.

As Kabaservice points out, Republicans were more reliable supporters of civil rights legislation than Democrats in the mid-1960s. Despite Goldwater’s vote against the civil rights act of 1964, Republicans as a whole supported this landmark legislation by a greater percentage than Democrats in both houses of Congress. Under the elder Romeny’s leadership, Michigan Republicans actively sought to build support in Detroit’s inner city areas, building on the fact that many African Americans had been taken for granted by the Democrats. When riots devastated  the city in 1967, a Republican storefront went untouched. Under the leadership of GOP state chair Elley Peterson, Republicans established outreach efforts in other urban areas. Richard

the city in 1967, a Republican storefront went untouched. Under the leadership of GOP state chair Elley Peterson, Republicans established outreach efforts in other urban areas. Richard Nixon, who ultimately embraced a strategy to attract whites, both south and north, to the GOP on the basis of a backlash to black gains, nonetheless appointed high level African Americans to key positions, advanced affirmative action, and tolerated—at least initially–George Romney’s decision to cut off funding for sewer connections in suburban communities guilty of housing discrimination.

Nixon, who ultimately embraced a strategy to attract whites, both south and north, to the GOP on the basis of a backlash to black gains, nonetheless appointed high level African Americans to key positions, advanced affirmative action, and tolerated—at least initially–George Romney’s decision to cut off funding for sewer connections in suburban communities guilty of housing discrimination.

By the time of Nixon’s re-election campaign in 1972, the GOP had turned right, and George Romney was no longer running HUD. Moderates continued to support civil rights actions, including some forms of affirmative action and busing to help achieve racial balance in schools—famously labeled “forced busing” by its opponents. By the 1980s, however, the Reagan administration had moved as far away as it could from post 1960s means of assuring integration, to embrace “color blind” policies that would appear, at least on the surface, race neutral.

Kabaservice’s book represents an important source for examining the language we use to describe contemporary politicians. Both Romney and John Huntsman have been labeled moderates by various reporters, but in doing so journalists obscure any true meaning of the word as it has been used within the GOP. Maybe “more moderate” would be appropriate.

Racial attitudes are not the only standard for measuring moderation, of course, but neither Romney nor Huntsman could be considered socially progressive by any standard. Certainly, Mitt Romney is no Mark Hatfield. He’s no Chuck Percy. He’s no Linwood Holton, the Virginia Republican governor who represented a different kind of southern strategy to the one the GOP ultimately embraced, one that would advance the aspirations of blacks to enter the middle class rather than to protect white privilege. Mitt Romney is no George Romney either. That’s to be expected at one level, since times have changed and sons need to distance themselves from their fathers (as the younger Bush did from his). Still, let’s not put Mitt into the moderate camp any more than we should put Gingrich in that camp just because of his early association with the moderate Republican Ripon Society, an association he shared with Hillary Clinton before she became a Democrat. Check out Kabaservice’s book for details.

Howard,

Having spoken with pride about joining you as “one of the two paid staff who got Nelson Rockefeller supported to be the candidate” in Connecticut, I am delighted to see your current writings. Playing the minor supporting role that I did, I retain the passion for the direction for the Republican party that seemed so promising in those days, and feel anger and sorrow at the loss of a player party to be taken seriously by thoughtful folk. My hope for the party now simply lies in the aging of blindly idealistic “conservatives” and the very gradual influx of younger voters. I sense the party feeling a “now or never” nervousness at relying on the prospect of succeeding with the current coalition of what I call the “idealistically selfish” with those folk who vote against their self interest in being lured by inflammatory socially punitive idealism. Again, it is good to see your careful thinking in print.

Best wishes,

Douglas Bond

a